- Home

- J. W. Mohnhaupt

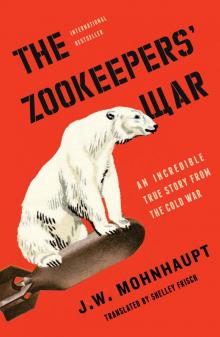

The Zookeepers' War Page 2

The Zookeepers' War Read online

Page 2

Katharina Heinroth had remarkable credentials herself. At the age of twenty-two, she had enrolled in PhD courses in zoology, botany, paleontology, geology, and geography at the University of Breslau, despite the dismal job prospects for a young woman looking to go into those fields. She collected four marriage proposals before graduation, almost as many as she did areas of academic interest, and her dissertation adviser often worried that with all the time she spent “going through men,” as he called it, she would not have enough time to devote to her studies. But after four years, she became the first woman to receive a doctorate at the university’s Zoological Institute—summa cum laude, no less. In the two decades since graduation, she’d spent her nights conducting research on bees and springtails (invertebrates less than a quarter of an inch long); during the day, she earned a living as a secretary, librarian, or administrative assistant. That was as far as a woman could go at the time.

* * *

While Katharina Heinroth put out the fire in the hippopotamus house, rumors circulated through Berlin that animals had escaped from the zoo. Elephants were said to be making their way across the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s main thoroughfare, and lions were roaming about the ruins of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. A tiger reportedly made it all the way to bustling Potsdamer Platz, ate a piece of traditional honey-glazed “bee-sting cake” in the bomb-gutted Café Josty, and promptly died for reasons unknown. But the animals who survived the inferno were too scared to flee: they cowered in the ruins. Even the vultures and eagles did not fly away, but remained on the branches of their shattered cages. A tapir—a tropical relative of the rhinoceros, but piglike in appearance—pressed up against the bars of its enclosure to draw warmth from some smoldering carbon piled in front of it. A crocodile was found lying at the entrance to the aquarium on Budapester Strasse. The force of the explosions had hurled it out of the tropical hall, and the night frost had been the death of it. Since the meat was kept fresh by the cold, the following days brought crocodile tail soup for the famished zoo staff, who were grateful for the added bit of meat.

Meanwhile, the air raids kept escalating. During the day, the Americans bombed Berlin; at night, the British took over. And every day, the Red Army moved closer and closer to the capital from the east.

So it went for eighteen months, until just before Easter of 1945, when Oskar Heinroth was slowly recovering from a bout of pneumonia. All the time spent in the cold air raid shelter had taken a terrible toll on the seventy-four-year-old aquarium director. He was getting an injection to help him back on his feet when the nurse accidentally hit a nerve and paralyzed his right leg. Katharina, who for so many years had supported her husband in his research, now added nurse to her responsibilities. When he developed a nutritional edema, she asked Lutz Heck for a daily ration of goat milk. But food was scarce, and the zoo director had never liked Heinroth’s pigeon research, much less his contacts with Jewish and dissident scientists.

The conversation quickly turned ugly, dredging up old resentments. “Herr Heinroth would have been better off sticking to his own job at the aquarium,” Heck said sharply. “In the future I’ll be sure that everyone’s research agenda is prearranged.”

“In that case, you can forget about any discoveries,” Katharina snapped back, restraint having never been one of her strong points. “No work of genius has ever come out of civil service!”

They argued back and forth for quite some time, until Heck gave in and authorized the goat milk for her husband. “I’ve never fought with anyone for so long,” he said, impressed. He wasn’t used to being contradicted, let alone by a woman.

Trenches in the Zoo

By late April, it was evident that the “future” Lutz Heck alluded to was not to be. Some obstinate souls who still believed in the possibility of a German victory attempted to keep the advancing Red Army at bay with antiaircraft guns. The huge flak tower in which these guns were housed was an obvious target, and many of the shots fired in its direction exploded in the adjoining zoo.

Heck arranged for his wife and sons to be evacuated and sent west. Katharina Heinroth was also trying to figure out how to get herself and her husband to safety. But Oskar could no longer walk. And even if he could have fled, it would not have occurred to him to leave the zoo, especially his aquarium, which he had run for more than thirty years. “Let’s stay here,” he said to her quietly. “I’d rather go down with everything.”

In the final days of April, the eastern front ran right through the zoo. Several Soviet tanks had already battled their way to its walls. The remaining zookeepers were conscripted into the German national militia, known as the Volkssturm, and had to dig trenches on the zoo grounds. During lulls in combat, they tended to the few animals that remained.

By the evening of April 30, it was clearly just a matter of time until the Red Army attacked the zoo. Lutz Heck bolted before they could. He sensed what lay ahead for him: the Russians had been told he’d seized animals from Eastern European zoos, and abducted a team of wild horses from Ukraine. With barely any working vehicles left in Berlin, he fled on a bicycle and succeeded in making his way to Leipzig, more than a hundred miles, where he rode to the home of zoo director Karl Max Schneider.

Schneider was surprised to open his door and see who was standing in front of his home. “As a fellow zookeeper, I’m asking you to put me up for the night,” Heck said, without further explanation.

Fifty-eight-year-old Schneider had lost his left lower leg while serving as a lieutenant in World War I. An old Social Democrat, he’d refused to join the Nazi party until 1938, when he succumbed to pressure from on high. He cast a skeptical eye on Heck before reaching into his pants pocket to pull out a keyring. “Here’s the key to my apartment,” he said, “but I will not spend the night under a roof with you. When I return tomorrow morning at six o’clock, you’ll be gone.” Schneider left, and spent the night with friends. When he returned the next day, Heck had vanished. He’d stay hidden for quite some time.

* * *

Smoke lay over Berlin. When the dull thuds of the explosions had at last gone silent, the grounds of the zoo had been reduced to rubble. Two stone elephants sat at the Budapester Strasse entrance like silent sentinels, the gateway they’d watched over destroyed, apart from a narrow crumbling arc somehow still balanced between two shattered pillars. The antelope house, originally built in the Moorish style, was now just a pile of debris with two minarets and a chimney sticking out. A young horse poked around for a trace of grass between heaped-up bricks, while an emaciated wolf gazed over from his enclosure, hungry but too weak to chase after it.

Once director Heck had fled, Katharina Heinroth took charge, tending to injured Berliners in the zoo’s air raid shelter—her dying husband among them. She had attached a white cloth with a red cross to the door of the bunker in the hope the Russians would spare them from combat operations. From his sickbed, Oskar instructed her how to treat gunshot wounds and apply dressings. A few hours later the first Red Army soldiers entered the zoo.

Oskar asked his wife for one last favor. “The poison pills,” he whispered, “get them for me.” But the pills were in a drawer in Oskar’s study in their demolished apartment. How was she supposed to get there? The place was swarming with soldiers, and besides, she had no intention of leaving her husband alone, so she tried to reassure him, telling him gently, “We’ll get through this somehow.” He sighed in disappointment.

The next morning, the soldiers herded everyone out of the air raid shelter. Katharina was able to carry her husband to a dry, quiet corner in the basement of the aquarium, but they were unable to stay hidden for long. As the days dragged on, different sets of soldiers made their way past the smashed walls, on the search for something to eat or drink, or just an opportunity to show the Germans who was now in charge. Men who did not obey, or tried to protect their wives, were shot, and their wives raped. Several times Heinroth and her husband moved from one level of the ruin to another, but they were found

again and again. “Raboti, raboti!” the soldiers shouted when they saw Katharina. The men held her down and raped her.

Finally, she was able to get her husband out of the aquarium. He was too ill to stand on his own, so she sat him in a wheelbarrow and went looking for a new hideout. But most of the cellars in the area were overcrowded. They had to keep moving on every few days.

Once the Soviet troops had left the zoo, Katharina Heinroth went back to her old apartment and put a room in some semblance of order. Then, with the help of two zookeepers, she brought her husband back home.

Oskar Heinroth died on May 31. Katharina was now alone. She asked the zoo’s carpenter to make a coffin out of doors from bombed-out buildings and had her husband cremated. Several weeks went by before she could bury him on the zoo grounds.

Now she had to go on, and Katharina Heinroth recalled the motto of her dissertation adviser in Breslau: “Doing something will make you feel better.” She had always abided by the saying, and it had helped her to cope with dark times in her life. So she and the remaining zoo staff set about making order out of the chaos. As they cleaned things up, they found the corpses of eighty-two people amidst the rubble. Like the dead animals before them, the bodies were buried in mass graves.

Only ninety-one animals had survived the war. These included a reindeer, a rare Oriental stork from Japan, a shoebill—a bird about the size of a crane, with gray feathers and a clog-shaped beak, whose natural habitat is the swamps of the Nile—the male elephant, Siam, and Knautschke, the young hippo. In the final days of the war, bombs had destroyed the hippo house and wounded Knautschke’s mother so severely that she died. The zookeepers poured water over Knautschke several times a day to keep his skin from drying out. Several other animals disappeared soon after, slaughtered by hungry Berliners. The rest of the animals were placed in temporary enclosures, the shoebill in one of the few undamaged bathrooms.

After Heck’s disappearance, the zoo lacked a director. The former managing director, Hans Ammon, had tried to take over, but once a former zoo chauffeur revealed that Ammon had been a Nazi party member, he was forced to leave—while the chauffeur was installed as head of the zoo’s cleanup efforts by the Soviets. He brought together two hundred Trümmerfrauen (“rubble women”), and by July 1, 1945, some semblance of a restored zoo could be opened. A few weeks later, yet another man turned up—a former part-time waiter in the zoo’s restaurant—who claimed to have been put in charge of running the zoo. Since neither the telephone nor mail systems were operational, no one could confirm or deny this. The bickering between the two “directors” resounded through the zoo for weeks. Still, they agreed on one thing: they sent Katharina Heinroth to work with the rubble women, where the most she was allowed to do was make a couple of signs for the animal enclosures.

While this rebuilding was underway, the governments of the United States, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and France formally assumed joint control of Germany, dividing the country into four semi-autonomous occupation zones. Berlin, located deep inside the Soviet zone, was also split into four, with one sector given to each Allied Power to administer. The Berlin Zoo suddenly found itself under nominal British control.

When the occupying forces got wind of the leadership chaos at the zoo, they charged the newly established Magistrate of Greater Berlin—the city’s highest administrative authority, tasked with overseeing all four sectors—with clearing up the matter once and for all. Shortly thereafter, Katharina Heinroth received a written request from the magistrate to appear at the Old City Hall on August 3. The request did not specify why.

Werner Schröder had also received a letter from the magistrate, and on the morning of August 3, he started out on the five-mile walk from his apartment in the district of Wilmersdorf to the city center. He was to report to the Public Education Department. He, too, was left in the dark as to why.

Werner Schröder had come in contact with Oskar Heinroth while he was studying zoology at Berlin’s Friedrich Wilhelm University in the 1930s, but he did not know Katharina. They met for the first time that day, when Josef Naas, head of the magistrate’s cultural bureau, informed them that Heinroth would serve as the interim head of the zoo and Werner Schröder as the managing director and her deputy.

Heinroth was well aware that she had been given this opportunity only because of the unusual circumstances of this moment in history: there were not enough politically untainted men to fill the country’s vacant positions. She’d later joke to friends, “They surely thought I was Oskar when they asked me to come to city hall.”

And so Heinroth and Schröder, who was also politically above reproach, set about rebuilding the zoo. Because the boundary walls had been smashed, street traffic ran right through the grounds. During the night, gangs came to plunder what they could. The zookeepers attempted to drive them away with whistles, but a silver fox, a wild boar, and a deer fell victim nevertheless.

In late September Heinroth was appointed the zoo’s permanent director, and a good month later the Allied Powers officially recognized the institution’s cultural value, guaranteeing public financing, which kept the zoo afloat—albeit barely. During that first year following the war, there was hardly any reconstruction. The sewer system and electricity supply had to be put into operation again, and there was little food for the animals. Vegetables were planted on the fallow lands, as was tobacco; cigarettes were an indispensable currency. Heinroth had signs made up to guide visitors through the muddle of half-destroyed cages and enclosures to find the ones in which animals were still alive. One day she caught a thief trying to make off with the wooden planks from a wrecked stable. When she confronted him, he snapped, “As a zoo shareholder, I have every right to do this!”

In January 1946 the Associated Press would write, “Only about 200 animals still live in the dreary ruins of this once so colorful and beloved institution.” Even so, things were much less dire than they had been the previous year. There was no money to purchase new animals, but several hundred Berliners had brought their pets to the zoo, especially their parrots, thinking they they could get better care there than at home. A giraffe named Rieke who’d been evacuated to Vienna was returned to Berlin, and the staff chipped in a month’s salary to acquire at least a few new species. Heinroth used the money to buy penguins. She also offered a consultation hour for worried pet owners hoping to find out why their parrot was plucking out its feathers or why their dog disobeyed them.

Cabbage for Knautschke

In late August 1947 the zoo was again rocked by explosions; British troops were trying to blast apart the nearby air raid shelter. All 649 animals had to be lured into wooden crates, one after the after, and brought out of the zoo. But the bunker was too massive, despite the twenty tons of explosives detonated. The attempt would have to be repeated the following year. By then, explosions were a minor concern compared to the new problems facing the zoo.

The blockade of West Berlin, which lasted almost a full year, posed entirely new problems for the zoo. The occupying forces had been arguing for years about creating a unified German currency, and now in June 1948 the three Western Powers announced that they would be introducing the new deutsche mark in their sectors of Berlin. The Soviets, who had not been consulted on this move, reacted promptly. On the night of June 23, 1948, the lights went out in the western part of the city, the electricity supply was switched off, and all streets and waterways were closed by the Red Army. The island of West Berlin, which depended on supplies from the outside world, was cut off from that world except by air. The Allies used an airlift to supply food to the two million residents.

The zoo was expected to do its part to save the city from starvation. The new British commander informed Katharina Heinroth what had to be done: fell all the trees, plant spinach on the open spaces, get rid of all the animals, and set up chicken coops instead.

Heinroth was shocked as she pictured the grand oaks falling, some of them four hundred years old. The zoo would have to close down,

and she knew that once a zoo had been closed, it was almost impossible to reopen it. She was painfully aware of what had happened in Düsseldorf, where the Zoological Garden, founded in 1876, was closed on what was supposed to be a temporary basis during World War II, and hadn’t opened its gates again. She wanted to spare her zoo—Oskar’s zoo—from that fate.

Heinroth resisted the order. She tried to stall, filing complaints at the headquarters of the British forces and at the Berlin bureau for open space planning. The commander relented, and again visited Heinroth at the zoo. This time he brought a map with trees sketched in. He asked her to mark the trees that absolutely had to be preserved. A major portion had been damaged in the war, with many treetops lopped off. But Katharina Heinroth marked every tree, without exception. The commander threatened her with legal action, but Heinroth stood her ground; she had argued with a whole host of characters over the years. Sometime later, she received a visit from another British officer from headquarters. “Forget about that business with the trees,” was all he said. In the end, not a single tree was felled.

* * *

In May 1949, the American, British, and French occupation zones coalesced into a sovereign state, the Federal Republic of Germany. West Berlin became a de facto part of this new country—although the Soviet Union would continue to dispute the city’s status for decades. Five months later, in October 1949, the former Soviet zone was rechristened the German Democratic Republic. East Berlin became the capital of the new socialist state.

The Zookeepers' War

The Zookeepers' War